- Details

- Written by: Ken Furtado

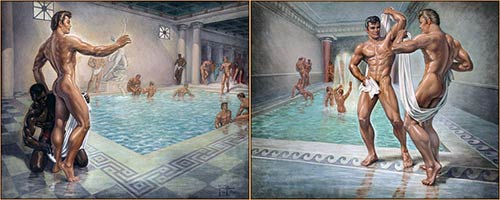

The next two lithographs were printed simultaneously: Baths of Ancient Rome and Spartan Soldiers Bathing. These were smaller than the previous pair, with the actual print area measuring 14x11 inches. Only 10 of Quaintance's 54 canvases of the Male Physique period had a horizontal or landscape orientation, and these are two of them.

The next two lithographs were printed simultaneously: Baths of Ancient Rome and Spartan Soldiers Bathing. These were smaller than the previous pair, with the actual print area measuring 14x11 inches. Only 10 of Quaintance's 54 canvases of the Male Physique period had a horizontal or landscape orientation, and these are two of them.

The black and white photos of these two paintings could never to justice to the subtle reflections in the water and on the tiles surrounding the pools, so this pair of canvases was an excellent choice to become the next two color lithographs.

- Details

- Written by: Ken Furtado

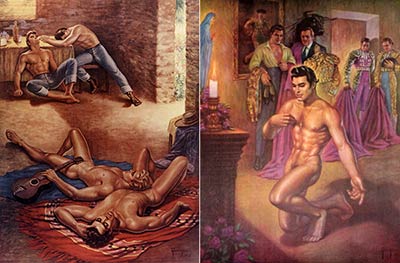

If asked to name Quaintance's masterpiece, most people will choose either Siesta or Preludio. Apparently Quaintance thought so too, because those were the first two canvases of his "Male Physique" period that he chose to reproduce as color lithographs.

If asked to name Quaintance's masterpiece, most people will choose either Siesta or Preludio. Apparently Quaintance thought so too, because those were the first two canvases of his "Male Physique" period that he chose to reproduce as color lithographs.

He had always sold 8x10 black and white photos of his canvases to a public that had an unquenchable thirst for them — his mailing list was said to number over 10,000 names. Later, acceding to the demand for color reproductions, he began to sell color chromes, or slides, of the paintings. But the lithographs were new territory. They were printed in full color that carefully duplicated the original oils and printed on heavy stock with a 16- by 20-inch print area and ample margins. The selling price was $5. After Preludio was issued as a lithograph, you could purchase both for $8.

- Details

- Written by: Ken Furtado

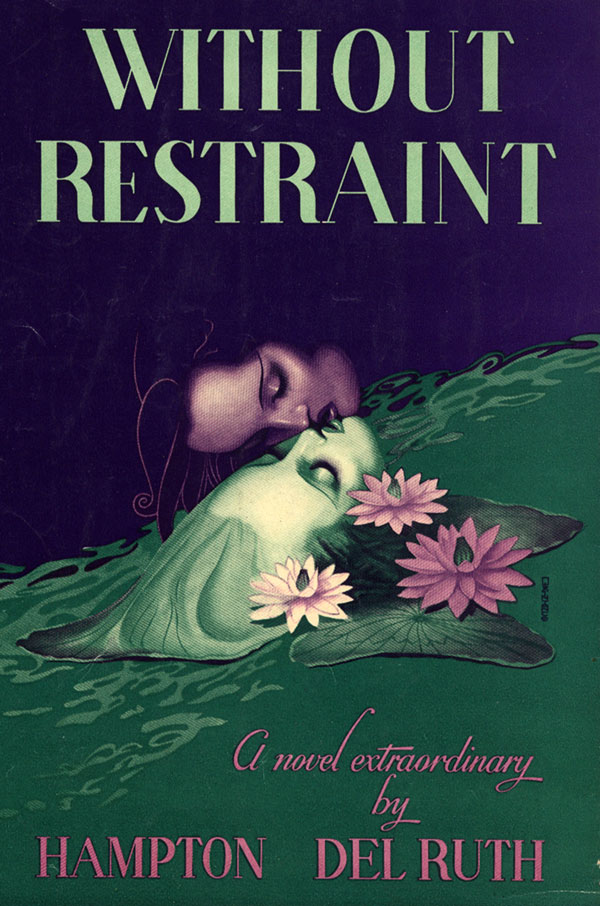

In the late 1930s, Quaintance was busily designing women's hairstyles and department store windows. At that time he also drew a series of faces that appeared on soap wrappers, novel dust jackets and as a series of lithographs. One of his employers was Robert of Fifth Avenue, located at 675 Fifth Avenue in New York City.

In the late 1930s, Quaintance was busily designing women's hairstyles and department store windows. At that time he also drew a series of faces that appeared on soap wrappers, novel dust jackets and as a series of lithographs. One of his employers was Robert of Fifth Avenue, located at 675 Fifth Avenue in New York City.

Different versions exist of these lithographs. In this article we'll consider Reverie and Illusion. Each shows a pair of disembodied male and female faces. The faces in Illusion are so androgynous that many viewers assume it is a lesbian couple. That would have been extraordinary for the time, since these lithographs were openly offered for sale in New York department stores. In both lithographs, the faces are complemented by flowers: water lilies in Illusion and petunias or hibiscus flowers in Reverie.

- Details

- Written by: Ken Furtado

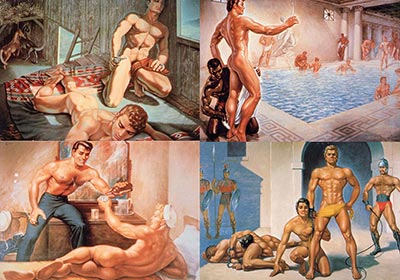

Back in 1981 or so, a "group of San Franciscans" founded an organization called the National Gay Art Archives. Proclaiming that George Quaintance was "the founding father of gay beefcake art," they submitted factually incorrect articles to several national gay magazines. One such article, published in issue #76 of In Touch for Men (February 1983), carried the byline of Ted Smith, a "founder and curator of the NGAA." Smith, according to one source, intended to write a biography of Quaintance but his life was cut short by AIDS.

Back in 1981 or so, a "group of San Franciscans" founded an organization called the National Gay Art Archives. Proclaiming that George Quaintance was "the founding father of gay beefcake art," they submitted factually incorrect articles to several national gay magazines. One such article, published in issue #76 of In Touch for Men (February 1983), carried the byline of Ted Smith, a "founder and curator of the NGAA." Smith, according to one source, intended to write a biography of Quaintance but his life was cut short by AIDS.

The National Gay Art Archives advertised "seeking original works by Quaintance & other Gay artists." Some naysayers claimed that this was just a group of guys hoping to get collectors to donate gay art to their private collection, which they were misrepresenting as a nonprofit organization.

- Details

- Written by: Ken Furtado

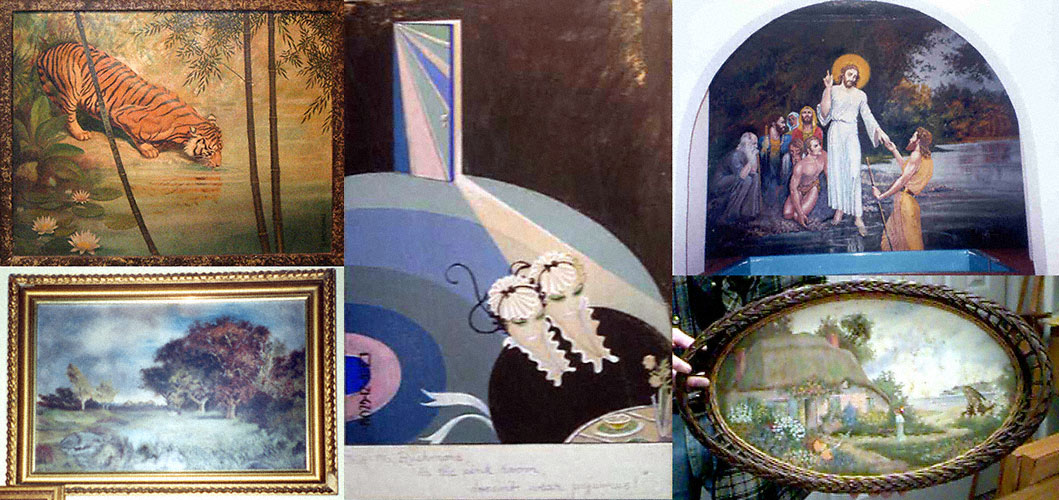

Quaintance painted many images that one would not normally associate with his name, and it might surprise many people to learn that he didn't paint male models at all until he was in his forties.

Quaintance painted many images that one would not normally associate with his name, and it might surprise many people to learn that he didn't paint male models at all until he was in his forties.

The single exception would be the mural he painted for the Stanley Baptist Church in 1933, at his mother's urging. The life-sized mural depicts the imminent baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist. Huddled on the shore are half a dozen worshippers — all male — one of whom is uncharacteristically clad only in a fur loincloth. That man is a thinly disguised version of Quaintance himself. This would not be the last time he painted himself into one of his canvases.

- Details

- Written by: Ken Furtado

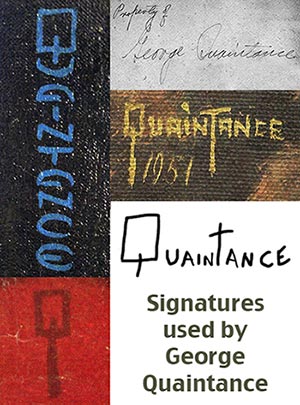

Over the course of his career, Quaintance used two basically different signatures. Initially, he painted his surname in squarish letters that ran vertically down the canvas. This remained his signature of choice until about 1942, when he adopted the signature most often associated with him: his last name printed horizontally, with exaggerated descenders on the "Q" and "T." The example shown (right, second from top) is an actual scan from the canvas After the Storm.

Over the course of his career, Quaintance used two basically different signatures. Initially, he painted his surname in squarish letters that ran vertically down the canvas. This remained his signature of choice until about 1942, when he adopted the signature most often associated with him: his last name printed horizontally, with exaggerated descenders on the "Q" and "T." The example shown (right, second from top) is an actual scan from the canvas After the Storm.

Sometimes, especially on magazine covers, he would use only the letter "Q" by itself.

For his sculptures, he used a stylus to scratch his name into the drying hydrostone, the plaster-of-Paris-like material that he favored for casting.

His actual signature is shown for comparison.